This is a three- part series of short articles on collective learning and the struggle for a new society. The first two parts are included in this post, and the third will be published later.

This is a three- part series of short articles on collective learning and the struggle for a new society. The first two parts are included in this post, and the third will be published later.

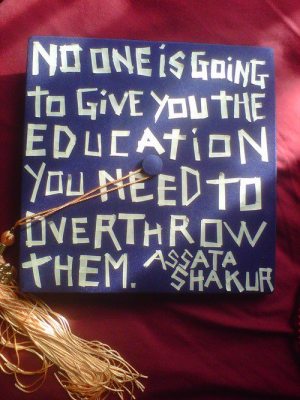

The first article is called “Steal the Ability to Read this Book”; it makes a case for seizing the reading skills that slave-masters and capitalist bosses have systematically denied oppressed communities. I will highlight the importance of literacy in revolutionary struggles today. I will also clarify that the type of literacy we are struggling for is not the same kind of top-down education that imperial NGOs and white-mans-burden style teachers want to impose on indigenous people, youth of color, and working class people here and around the world.

In the second article, I respond to critics of my article Between the Leninists and the Clowns. In that piece, I had argued for a process of collective learning/teaching within freedom movements, but critics interpreted this as a call for importing formalized, classroom-style teaching into movement circles. In this follow up piece, I clarify that we’re actually trying to develop a learning praxis (reflective practice) that can break from the alienated and oppressive dynamics of capitalist classrooms. I argue that as a teacher, the last thing I want to do is to bring more high stakes, standardized, impersonal, and alienated teaching into the movement. After all, we’re building the movement in the first place in order to struggle against the alienation of labor, and all of those pressures and expectations are the kind of alienation I’d like to leave at the classroom door when I check out from work. On the contrary, movement study groups show us what free learning could be like if the capitalist education system were overthrown and replaced by a new way of creating knowledge together.

The third article is more practical, and it will hopefully come out in the upcoming months since it is a reflection on this ongoing praxis. I will argue that how we read to make a revolution is different from how we are taught to read in school, and that the specific revolutionary reading strategies we all use need to be explicitly stated and shared with each other so that more people will have access to them. I attempt to outline some of the more revolutionary reading strategies that I’ve learned and co-created, in the hope that others will build upon these and share their own.

I will also share some of the revolutionary curriculum that BOC has developed as we’ve done this ourselves within our collective. I’ll focus on how we share literacy skills within the group, and how we integrate reading and writing skill development with strategic and theoretical research and discussion; this allows us to develop skills without relying on the kind of patronizing workbook-style lessons that turn so many people off from reading in the first place.

People in our group have a wide range of formal (mis)educational backgrounds, from inner city high schools to prestigious graduate schools. As far as the system goes, some of us were trained to write books and others were barely taught to write at all. The goal of our study group is to overcome these inequalities by sharing skills and creating knowledge together. I hope to share some of our methods for doing this, so that other collectives, organizations, communities, and affinity groups across the country can build off of these if you find them useful. I hope this will encourage other groups to critique and improve our methods and also to share your own so we can begin to build off of each others’ efforts.

Part 1: “Steal the ability to read this book”

Note: The process of producing this text is an example of the content and argument of this series of articles. I asked several high-school aged youth with a variety of reading skills to give me detailed feedback on a draft of this article, just like I do when I read their work. They highlighted what they agreed with, what they disagreed with, and what confused them in different colors and then we discussed it. I revised the text based on their feedback to make sure it is accessible, because I want folks to be able to use in struggles around public education.

This is an example of what educators call a considerate text, meaning a text that is written to be as accessible as possible to folks with a variety of reading skills. I would argue that revolutionaries should hone our ability to create texts like this to make our movements more accessible to people of all ages and abilities. We should be able to break down just about any complex concept, without “dumbing it down” in a patronizing way (as Lupe Fiasco put it, “they told me I should come down cousin, but I flatly refused, I ain’t dumbed down nothin'”). In other words: keep the complex content, but define key vocabulary, revise long or confusing sentences, and make sure each concept builds off of prior knowledge. The process of asking youth for feedback also modeled for them how to effectively revise a text in light of the needs of a real-life audience, and showed that writers continue to learn no matter what age we are, because writing is a social and communal activity.

—————————

There is a reason why the slave masters made it illegal for slaves to learn to read. In the hands of oppressed people, written words can be revolutionary. They were back then, and they still are today.

Of course, the written word would not be powerful without the spoken word. Spoken words have always been a weapon of struggle, from the storytelling of the West African griots through tales of resistance told in code on the plantation so the masters couldn’t understand.

But the written word builds off these oral traditions in equally powerful ways. It allows oppressed people to communicate with potential comrades who are not immediately in their presence – and that’s crucial when they’re trying to overthrow a global system of oppression. It allows for stories of events like the Haitian revolution to spread to places like the plantations of the US South, inspiring uprisings there, even if people there had never met someone who had participated in Haiti’s revolt against slavery. Texts like Walker’s Appeal, smuggled into the US South, were powerful calls to rise up, calls that the masters needed to silence at all costs. Hence, the masters imposed illiteracy – they made sure potential rebels wouldn’t know how to read these revolutionary texts.

That forced illiteracy continues today with school systems that put a lot of effort into training students to be good capitalist workers – or future obedient prisoners. They do this instead of teaching students how to teach themselves to read. They present reading as something that is boring, dry, and whitewashed, instead of showing students how to love reading, and how to find strength in it over the course of their lives. This is especially true for Black youth, and youth who are economic refugees from the places around the world that the US dominates through its empire. As Dead Prez put it, “They schools ain’t teachin us, what we need to know to survive. They schools don’t educate, all they teach the people is lies”.

Or, as bell hooks put it in a review of the book Night Vision:

The primary site of genocide for black people right now in America is the public school system. It’s not poverty: Black people have always been poor. Masses of black people are richer today than we’ve ever been in our history in this country. So the question is not a genocide that is rooted simply and solely in poverty, it’s the condition of the poverty. I grew up in the midst of poverty but every black kid that I knew could read and write. We have to talk about the fact that we cannot educate for critical consciousness if we have a group of people who cannot access Fanon, Cabral, or Audre Lorde because they can’t read or write. How did Malcolm X radicalize his consciousness? He did it through books. If you deprive working-class and poor black people of access to reading and writing, you are making them that much farther removed from being a class that can engage in revolutionary resistance.

To different degrees, this is also true for working class youth in general. Instead of learning to produce and read texts like Walker’s Appeal, schools either fail to teach youth to read, or they teach youth to read texts like the boring instruction manuals their managers will give them at work. Neither of these is an example of the kind of revolutionary literacy that a new generation of youth could possibly use to start a revolution at a scale even larger than the one Walker called for. When bell hooks talks about “critical consciousness” this is what she means – awareness of what’s really going on, and the ability to criticize everything that holds us back and holds us down.

We do need to be cautious about celebrating literacy, since our enemies also claim they are bringing progress to the world by teaching people to read and write, and they use that as an excuse to invade countries and take them over. When white colonists came and took over Native lands, they tried to destroy Native societies by forcing Native youth to speak European languages and to learn to read and write in those languages. They set up boarding schools that tortured students – they were brutally punished for speaking their own languages. This was a genocide- the attempted destruction of entire peoples. The system did not want Native peoples to pass down their own knowledge to the next generation. When we argue for literacy (the ability to read and write), we must make clear that we are NOT justifying this kind of colonialism. Teaching people to read and write should never be used as an excuse to dominate or colonize anyone. We’re simply arguing that those who want to learn to read and write should be able to – especially if they want to learn to read and write about how to overthrow the colonial system and its racist schools.

The need for literacy today is even greater than during the days of slavery. Today, we are bombarded with the written word: text messages, facebook status updates, newspaper headlines, emails, etc.

Not to mention the fact that literacy can help us come together when we are all so spread out from each other. In the U.S. today, there are not as many concentrated factories or neighborhoods where communities of resistance can form. When the police attack your family members, or when your friend is killed by an injury on the job, you can’t just shout “strike” down the assembly line, or you can’t just walk out into your street and rally your neighbors together. Now, communities are spread out because of rising rents, forced migration, and the breakup of large workplaces into small shops that are part of assembly lines spread out around the world. People commute long hours, and live farther away from family and friends. Many work in other countries and send money back home, reading newspapers in multiple languages to find out what’s going on. There are still communities that organize themselves, but at a much larger, sometimes global scale. This affects the way movements emerge today, relying increasingly on letters, phone calls, internet communication, and independent media production.

Of course there are still billions of people globally without internet access. Most of their information comes from word of mouth or TV. Movements need to figure out how to build their own (guerilla) TV and radio stations, like when women in Oaxaca, Mexico occupied the local TV station in 2006 and used it to spread the uprising that was happening there. But in the meantime, it seems that a lot of struggle will be connected through word of mouth, with some people engaging in that word of mouth communication also, at the same time, communicating with each other globally through writing on blogs, twitter, emails, facebook, and independent newspapers. So the network of written communications will likely influence the word of mouth networks, and vice versa. It’s important that the folks with literacy skills share these with folks who don’t have them, so that a few people don’t dominate by controlling communication among the various networks. While that process is unfolding, it’s also important to organize ourselves in ways that support communication among people in different areas who don’t have literacy skills.

The written word is also powerful because it can be more anonymous, making it harder for the government to track you down and put you in prison for writing something controversial. Also, something like a blog or ‘zine requires less specialized skill (and less expensive equipment) to start than something like a regular video news site or guerilla radio station.

Literacy is also necessary simply to understand the confusing complexity of the networks which contemporary capitalism uses to sustain itself. If you want to rise up and, say, shut down the ports like the West Coast Occupy movement did, you have to take out a map and read it, because the port is spread out across a concrete jungle of freeways and railroad tracks.[1]

So, in general, we need literacy in order to sort through the massive amount of information required to self-organize a movement under today’s complex conditions. Again, that’s exactly why the capitalist education system is NOT sharing that literacy equally, and that’s why it’s important for revolutionaries to seize that knowledge if we don’t have it already, and to share it with each other. We can’t rely on the school system to do it for us.

Of course, I’m not saying anything new here. Working class communities, especially Black communities, have been fighting the public education system for over a century, demanding access to literacy. This struggle was a central part of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. Whatever meaningful learning can go on in public school classrooms is largely a result of this self-organizing and the pressure that students, their families, and teachers have put on the system.

Some of us might struggle to learn to read in schools. Others might learn to read outside of school like Malcolm X did. In any case, learning to read like Malcolm, with joy, curiosity, and drive, is crucial if we want to become organic intellectuals: smart, strong working class people who will have a shot of making history and changing the world for the better.

Part 2: Clowns to the left of me, Leninists to the right, here I am – chillin and reading with you…

About a year ago, I met with working class youth of color in Queens, NY who are part of the Queens Radical Crew and the Fire Next Time network . They were doing study groups on Marxism, Malcolm X, and various novels with friends in the neighborhood and in nearby housing projects. As we ate dinner, they picked my brain, asking me every question they could think of about our struggles in the West Coast Decolonize/ Occupy the movement, Marxism, feminism, religion, etc. I also had a lot of questions for them, especially about how they conducted their study groups, and the similarities and differences between New York and Seattle. These comrades are simultaneously students and teachers – learning and sharing what they learn, creating new knowledge together, and creating a subversive working class intellectual culture similar to cultures that have been an explosive part of past movements, from the IWW to the Black Panthers. They are not reading for school or for work – they are reading for revolution. We are trying to do the same thing here in Seattle.

This conversation was one of many experiences that inspired me to write Between the Leninists and the Clowns. In that piece, I argued for a process of collective learning and study aimed at overcoming some of the inequalities produced by the capitalist education system:

“The capitalist system does not prepare us all equally for the kinds of tasks that we want to do in the movement. Capitalist education reproduces racial and gender divisions of labor – some of us are trained to speak publicly in front of crowds while others are trained to wash dishes and make coffee. Some of us are trained to strategize in real time under pressure, and others are trained to listen and empathize. Some of us are trained to defend ourselves and each other from physical attack, and others are trained to write about that sort of thing. These skills are not always mutually exclusive, but few of us entered the movement well-rounded enough to do all of these crucial things, and all of them needed to be done.”

Some thought I was elevating flashy interventions like public speaking over other less celebrated but equally crucial movement activities. I wasn’t – in fact, I think that public speaking is a tiny part of what goes into being a revolutionary. The vast majority of our day-to-day time and energy is actually spent buidling relationships, getting to know new people, caring for each other, building teamwork and camaraderie, and supporting each others’ growth. All of this can be very difficult at times, and we are bound to make mistakes, especially since this sort of thing takes skills which capitalist schools often don’t teach us. Our goal should be to learn these from each other so that we can each become more well-rounded with greater capacities; so that we can be people who can, for example, take care of each others’ kids while strategizing together under pressure. That’s why I argued that “We need to set a basic standard in the movement – if you have an education (whether you got it in college or in prison), and you are not sharing this with at least one other working class person, then you are failing as a revolutionary and you need to check your priorities.” By education, I meant the full set of capacities, knowledge, and wisdom that go into living life and struggling together.

Some suggested this was an argument for BOC or other “cadre organizations” to assert our leadership over the movement in order to patronizingly teach others how to organize better. This was not my intention; trying to develop a set of professional movement managers would go against our autonomist principles, and would also be impractical, unsustainable, and frankly quite boring and painful for reasons I’ll lay out below. My whole goal in writing this was to propose movement-wide forms of collective, horizontal learning from each other. The learning currently done in small collectives is a necessary, unique, and important part of that, but it’s not the only valid form of learning. The only reason why I’ve tended to focus on learning in small collectives is because of lack of capacity, lack of time, and lack of broad interest in this sort of thing. As the movement grows and as we grow, I’d also love to do broader and larger learning projects.

Rather than promoting a professional leadership, I was warning against a situation where any entrenched leadership group could emerge by monopolizing strategic skills and communications channels within movement networks. Collective study was already going on in Seattle at the Free University and many other places which I should have acknowledged in my piece. Nevertheless, I still think we need to sustain and expand this in order to make the slogan “we are all leaders/ we have no leaders” a concrete material reality instead of an inspiring myth.

I also think it’s important to integrate study with strategizing, instead of separating them into different organizational forms (e.g. “come to this meeting if you want to get shit done” vs. “come to this meeting if you want to talk theory”). Because we live in a capitalist society that gives us little free time, practical considerations will sometimes require that we temporarily separate strategizing from organizing, or that we go through periods where we emphasize practice over theory or vice versa. But when they are permanently separated to the point where there is a frozen division of labor in the movement between who thinks and who acts, then this risks reproducing the capitalist splits between the classroom and real life, between mental and manual labor, between the mangers who devise the plan and the workers who take action to carry it out. I lay out this argument in more depth here (in the section on the “Thinking classes and the working classes”).

Needless to say, this division between the thinkers and the doers was part of the core ideology of the Stalinist parties in the 20th century – the party (pseudo)scientists devised the party line, and the workers carried it out. We still live in the memory-shadows of that disaster, so we are right to be a bit suspicious of self-proclaimed theoreticians. But can’t stop there and wallow in anti-intellectualism. The only way to prevent a new authoritarian leadership from emerging is to make sure that the same people who actually make the struggle happen have the theoretical skills to outsmart and outmaneuver anyone who tries to co-opt our efforts in order to build the next Politburo on top of our backs.

The problem of college educated revolutionaries

Will, from the Queens Radical Crew/ Fire Next Time, also argued for a revolutionary learning process in his provocative piece The Left’s Minstrel Show: How College Educated Revolutionaries of all Colors Keep the Working Class Shucking and Jiving. He pointed out how most radical scenes in the US are dominated by college educated revolutionaries. He argued that these revolutionaries tend to monopolize knowledge by sabotaging attempts to develop collective learning within the movement. They come up with all sorts of arguments against study and sharing knowledge, while quietly reading in private at home, sharpening their own strategic skills without sharing them. Because of their own alienating experiences in college, they argue that “authentic” working class people are turned off by reading and study; this leads them to treat intellectuals from oppressed communities as if they are no longer authentically part of these communities simply because they study and can hold their own in an intellectual debate with the college educated. All of this creates a hostile environment for working class intellectuals, and amounts to a situation where working class folks are expected to “share their experiences” of oppression and trauma, but not to analyze and draw their own conclusions from these experiences. That powerful task is left up to the college educated, who end up speaking for oppressed people no matter how much they claim they are doing exactly the opposite.

Will possess the same solution to this problem that I posed in “Lenin and the Clowns”: those who have an education should share it and should support folks who are trying to teach themselves outside of the framework of the capitalist education system.

Beyond the politics of guilt

And anarchist comrade wrote a thoughtful critique of the approach Will and I are arguing for:

“The tactical suggestion for revolutionaries “leaders” to formalize into cadres in order to educate the working-class on how to lead will not only reproduce our alienation, but exasperate it. By acting from a sense of revolutionary duty or moral obligation we re-create the same alienating dynamic of work. Tasks that should be enjoyable in their own right become obligatory, done with an “If I won’t then who will?” mentality. Acting from guilt places a morally righteous value onto our activism-as-atonement. Instead of selling our labor to bosses we donate (sacrifice?) our time to the “movement”. Exhaustion and fatigue become badges to be worn, proof of our devotion. When anarchists say “Give Up Activism” we do not mean the title, we mean the practices of morally righteous self-sacrifice.

“We have to invent a form of war such that the defeat of empire will no longer be a task that kills us, but which lets us know how to live, to be more and more alive” ~Living & Wrestling, Tiqqun

We shouldn’t share our skills out of some sort of revolutionary duty, but because we enjoy spending time together. Our “failure” as revolutionaries is not from a lack of peer-to-peer education, but when we act from a sense of moral obligation instead of shared desire. We need friendships that matter, based on shared desires and mutual understanding of one another’s differences and agreeances; not feelings of guilt or obligation toward each other. Our methods of fighting this society need to carry the relationships we desire within them. Only in this way can our struggles be carried out with joy, free from the moral baggage of duty & sacrifice.”

I also want to build a revolutionary struggle based on our desire for freedom, not a sense of guilt, sacrifice, or moral obligation. When I study each week with members of BOC who have not gone to college or graduate school like I have, I am not doing this out of a sense of guilt or a desire to atone for my educational privilege. I’m doing it because we’re friends, and we enjoy reading together. It is a two way street – I’m not “serving the people” or dragging myself to a meeting … we are learning from each other. I’m excited by what they have to say and I can’t wait to see what happens when they sharpen their reading and writing skills so they can communicate it to large numbers of people across the world.

I’m a teacher for my day job, and like any labor under capitalism, that work is alienated. The last thing I’d want to do is to turn the movement into an extension of my job. Of course, there are moments of joy and freedom in the classroom, mostly when my students organize themselves and start to push their learning beyond the bounds of what is expected in a public school classroom. But even with these moments, the work is still alienated because I’m always looking over my shoulder wondering if a district administrator will walk in and accuse me of unprofessional behavior because I am not asserting enough authority over my student’s thought processes. Even when the administrators are not there, their presence is felt like a panopticon eye – they’ve made it clear that my ability to share (and control) knowledge is constantly being assessed as a comodity on the market. Even natural human interactions like expressing care and support for my students become points on a rubric to be rated and evaluated as part of a high stakes test of my ability to teach.

And movies like Freedom Writers throw in a little white guilt to sweeten the deal – teachers are told if we don’t work 70 hour weeks to uplift youth of color from poverty then we are part of the problem (of course the racist people who make these movies have zero faith in the ability of youth of color to self-organize and solve their own problems and assume they need a nice white lady to do it for them).

The last thing I would want is to perpetuate this kind of high stakes, self-conscious, anxiety-driven, alienated, patronizing, standardized teaching within the movement. I tend to avoid scenes within the movement where this kind of guilt, obligation, and condescension already reign supreme, because I deal with enough of that on the job, and I’m not trying to sign up for a second work shift on top of the hours I already give to the system. I’m not a masochist and I want to sustain the joy that has motivated me to say in the movement for the past 10 years. Without that, I’ll burn out.

Chillin and reading with you

One of the main reasons why I’m NOT burning out is that our weekly BOC study groups are actually quite a relief from classroom teaching. In fact, they are a place where we can learn and teach each other in ways I wish we could in the classroom. At the most basic level, they are different from the classroom because everyone actually wants to be there.

I see us continuing the working class intellectual culture expressed in texts like the Johnson Forrest Tendency’s classic pamphlet The American Worker, written by Paul Romano, an assembly line worker in the Detroit auto plants. Romano and many other workers developed themselves as writers, theorists, and strategists through the JFT’s Third Layer School, and used this education to articulate dynamic and emerging elements of revolt that the mainstream, class-reductionist pre-1960s Left was ignoring (including their own emerging revolts as women, Black folks, and youth). They were way ahead of their time. I hope we can build something like that today.

Romano’s analysis of his own experience on the assembly line has also taught me something about my experiences in the classroom and in revolutionary study groups. Romano describes how auto workers would try to revamp the assembly line, making unauthorized changes to the production process. They wanted to take control of the machine so they could express an ounce of creativity during the hours of their lives they sold to the company – they refused to let the machine dominate them on its own schedule. He also describes how they would go home on the weekend and work on cars for fun. Why would they do the same thing they do at work off the clock? Because this was a moment where they could do it freely, on their own rhythm, without sacrifice, without a boss looking over their shoulder.

That creativity should be possible every day but it is robbed by the control systems of the capitalist workplace. So we try to find a little free time on the weekends where we can live creatively and uncontrolled, learning as we build. I see our revolutionary study groups as something like that. I leave work behind and have the opportunity to do what I do on the job without it being work. I catch a glimpse of the kind of free, creative, collective learning/teaching that I will be able to do throughout the week once the capitalist education system is overthrown and the division between life and the classroom is abolished.

So when I talk about revolutionary education, I’m not talking about a process of top-down indoctrination or academic elitism. When I talk about reading and studying together, I’m talking about reading in ways that build up our creative capacities to think and act together in unexpected, chaotic, and contradictory situations, so that we can actually practice collective autonomy in the real world, in real time – so that we will be too smart to get stuck in anyone’s dogmas, including the dogmas that we tend to impose on ourselves if we’re not careful.

[1] Video projects like Metropolis by Tides of Flame (link) also help address this challenge, but the production of this sort of video requires literacy.

Since I wrote this a comrade mentioned that it is strong on theory but short on strategy, and that it appears to argue for abstaining from struggles to defend or transform public education. I wanted to write a quick follow up clarifying my positions on these issues.

I disagree with comrades who argue against any type of intervention in the schools or who suggest it’s hopeless to try to transform them in the short term.

I’ve laid out a strategy for organizing in the schools in this piece: http://creativitynotcontrol.wordpress.com/2013/02/28/in-the-wake-of-the-testing-boycott-a-10-point-proposal-for-teacher-self-organization/

and in this one: https://blackorchidcollective.wordpress.com/2012/09/14/the-chicago-teachers-strike-and-beyond-deepening-struggles-in-the-schools/

I’m part of a new and small (so far) grouping called Creativity not Control that intervened in helping spread the MAP standardized testing boycott this spring (we didn’t initiate the boycott but we helped out, using some of the tactics outlined here: http://creativitynotcontrol.wordpress.com/2013/01/19/test-post-2/ and the flyers here: http://creativitynotcontrol.wordpress.com/flyers/).

We are currently brainstorming a long term campaign that could attempt to put these kinds of strategies into practice more consistently. I’ll write about this more if it starts to get going – right now we’re still in the brainstorming phase.

Also, I wanted to clarify that I don’t think all teachers are inherently, statically, or personally racist. The system itself reproduces social relations of white supremacy and we are part of that and need to challenge it through struggle. I also agree we need to engage with and support the mass struggles defending and transforming public education, especially the walkouts and occupations lead by working class youth of color. These struggles seem to be on the upswing, and it’s an important historic moment. “Steal the Ability to Read this Book” is meant to be an argument in support of these kind of struggles.

I also support the kind of organizing done by groups like Classroom Struggle in Oakland, especially their recent victory defending adult education classes: http://classroomstruggle.org/

I disagree with people who advocate an immediate abolition of education – while I do think the schools needs to be transcended in the revolution, this is a process, and it won’t happen overnight. In the meantime, we need a clear strategy for organizing in and around the schools, both for our own survival and to pave the way for that kind of transition. Ultraleft/ autonomist critiques of union-centric organizing or leftist business as usual should not lead automatically to an abstentionist “abolish education now” perspective… they can also lead to new types of practical and creative engagement in struggles inside the schools, just like autonomist Marxism contributed to discovering and engaging with new types of struggle in the factories.

The point I’m making in this current post, is that we ALSO need to engage in revolutionary education outside of the schools to build our own capacity to struggle and to see dynamic openings where working class self-activity can break through current limitations. That will hopefully have practical effects by making us stronger revolutionaries who can develop and carry out strategic organizing within the schools, without getting burnt out, isolated, or coopted into reformism.

The internal study life of our groups can also prefigure (in a dialectical way) the kind of learning we aim to do in the new society, and can thus give us a deeper focal point and sense of direction in the broader struggles in and around the public schools. At least that’s been my experience the past 6 months, and I’d recommend it to others.

Wonderful piece comrade, I am sincerely interested in how autonomy has become a defining part of you and your groups studies. As for the dynamic of intellectuals strategizing, and the workers carrying out the plan, I am in utter agreeance. We must all take part in every vein of the revolutionary circulation. What has worked for you, over everything else, to keep your collective moving forward?

Thanks Brother T. In terms of autonomy, the main things we’ve learned have been from practice – experiencing mass autonomy during the Occupy Movement, anti-austerity movements, anti-police movements, etc. in Seattle and the West Coast broadly. We’ve seen the power of oppressed people to self organize, and we’ve experienced our power as part of that. In terms of theoretical bases for autonomy, we draw a lot from the works of CLR James, Grace Lee Boggs, Raya Dunayevskaya, and Selma James (the Johnson-Forrest Tendency),and we draw more broadly from pro-autonomy currents within the Black liberation, labor, and feminist movements they were a part of. We also draw from Italian autonomist Marxism/Opiearismo and post-Opiearaismo. We are learning right now from indigenous struggles going on here and around the world.

I’m working on Part 3 of this series, and I hope it will answer your question about how we keep moving forward. We’ve faced a lot of challenges this year, and we are still struggling to figure out a new strategy after the collapse of Occupy and fragmentation of post-Occupy networks, so we don’t claim to have any perfect model to offer for how to build a collective. Broadly, we try to focus on organizing, meeting new people, studying together, building a social life together, caring for each other, joining and intervening in mass ruptures when they occur. We try to balance these activities on a week by week basis, but that’s easier said than done.

What has worked for you in these regards ? Any other readers have thoughts on these questions?

Well, working on a weekly basis is extremely important. Practice and experience are the key to progress, in my estimation. What I am interested in, is what exactly do you believe, is the most efficient way to spread a message of solidarity? We have tried handing out literature to youth in our community, but this has proved basically fruitless. What dialectics, phrasing, or approach has worked for your collective? How did you overcome the difficulties, public outreach propose?

I hear that. Where are you located? What kind of collective are you building?

In terms of your question, I think it’s important to engage in some type of organizing campaign. Passing out flyers to youth can be good, but if the flyers are not related to some type of ongoing struggle against the system, it’s hard to build ongoing relationships. We tend to try to collaborate with other groups and individuals to help build campaigns, even if we don’t agree with them on everything. If we agree with the overall message of the campaign’s literature, then we pass that out. Sometimes if we think something is missing, we’ll also make our own literature on the struggle and pass it out, or we’ll distribute both.

If we meet folks in the struggle who are interested in revolutionary politics and who want to study then we do one-on-one study groups with them. This is as much about building relationships as it is about the study itself. During times of larger upsurge, like Occupy, more folks become interested in revolutionary politics, so we’ve tried to do larger study groups.

It’s also important to just hang out and chill with folks independently of study and organizing, to build community and friendships over the long haul.

Shit, I didn’t realize you’re with the Queens Radical Collective! I’m sorry, I though you were someone else – I should have clicked on the website link on your avatar. So disregard my last message then – you all are already doing the study groups and hanging out, building with people. I’d say basically just keep doing what you’re doing, especially the study with your friends and acquaintances. That will probably be more fruitful than the flyering to youth you don’t know yet, because you already have a basis for some trust and communication. And if your friends can get to the point where they can do the same with their friends, then your milieu will expand. It will just take a while, but over time I think ya’ll will grow. But the flyering to youth on the corner or at a school, etc. can be good too, even if it doesn’t bring folks around – it sharpens your own skills to answer the kinds of questions folks will raise when they meet you. Whenever we do that, we try to do a collective reflection on it afterwards to think about what kinds of questions we want to go back and study so that we can communicate with people more effectively the next time around.

In terms of a campaign, it sounds like the hard thing in NYC might be finding other groups to work with since it seems like the Left is more fragmented there and everyone is so spread out through the different neighborhoods. Seattle’s a lot smaller so it’s a little easier here. I’d caution against launching a campaign yourself unless you have enough people to do it – that can be a recipe for burn out. Maybe you can find something smaller and winnable to start with and build from there, or if a larger struggle emerges you might be able to participate and help build it. Of course, sometimes you just have to fight because your own crew is under attack – like when one of us was facing deportation here. I know ya’ll were thinking about struggling on one of your jobs, how’s that going?

Also, did you meet folks through the Flatbush struggle? How did that go? Did you all meet folks there? Did any ongoing anti-police brutality struggles emerge out of it?

Anyway, I’m glad you liked the piece – thanks for the inspiration! If you all have any writings you’d like to share, on this topic or any other, we can cross- post on this blog to help spread the word through our networks here on the West Coast.

Queens, NY. The collective we did have, was supposed to be about learning, and outreaching. We also had several study groups that a few members were offering to facilitate. One on one study groups are fantastic. Personally, I like taking notes of the process, to use throughout the week. Using an email thread everyone is connected to, in order to circulate what we learned or analyzed.

Five out of seven in our collective stepped away for the summer, so for now I’m just trying to connect with people while I’m out, or commuting to wherever. It is so difficult to guess at who you think will want to listen. When with friends I find myself talking about this stuff loudly, in order to see which strangers are looking over in disgust, or in interest. Looking for guidance.

That’s a good idea, to take notes on what you’ve learned in each of the study groups. That could be the basis for future writing projects – pamphlets, blog posts, flyers, etc, which might also help you meet new people. I hear you about comrades stepping away for periods of time, that’s been happening here too – folks have family, work, job training responsibilities, etc. and a lot of folks have had to leave town for various reasons. Even if you just have a few people who keep going though, it’s possible to meet new folks and build with them, and some of the folks who stepped away will probably come back down the road.

That’s an interesting idea, trying to meet people by talking with friends on public transit, and seeing if strangers want to join the conversation. I’ve had some success with that here, having conversations on the bus. I’d always have flyers on hand in case I met someone who was interested in getting involved, so they could contact us, kind of like an “anti-business card”. Again, it’s a bit easier here because it’s a small city so sometimes you meet the same people each day on the bus.

Any other readers have thoughts on the questions Brother T is asking? What’s worked for ya’ll?

Hey brother, everything you said is awesome and I would like to think I follow those same guidelines. Thanks for your encouragement and advice.

You’re welcome. Good luck with all of this, and feel free to contact us any time to brainstorm/ collaborate

Pingback: Reading for Revolution (Parts 1 and 2) | Creativity Not Control

Pingback: BOOK 6: Storming Heaven | sd studygroup

Pingback: How to Assassinate Boredom: Reading and Writing our Lives | Creativity Not Control

This is a great thought provoking piece. Have you had a chance to revisit the topic to write a third part??

Thanks. Yes, I just finished the third part, which includes more specific reflections on revolutionary study sessions, and some study materials we’ve used in our groups here. It will be coming out in the journal Perspectives on Anarchist Theory within a few weeks, and I’ll repost it here.

Pingback: Reading for Revolution Part 3: DIY Strategies for Study Groups | Black Orchid Collective

Pingback: Zine version of Reading For Revolution | Black Orchid Collective